Frank Grierson of Russell Ave. was a labour pioneer

Ken Clavette

Earlier this year, the largest public sector strike in Canadian history took place; 155,000 members of the Public Service Alliance of Canada walked off the job. The roots of that strike and indeed of the unionization of federal workers can be traced back 116 years to a Sandy Hill resident named Frank Grierson.

Born in Halifax in 1865, Frank had an unhappy home life that led him to leave at an early age. He did return to Halifax long enough to meet a young socialite named Frances “Dot” Lawson before going west to search for his fortune in mining. In 1897, Dot’s father died. Upon hearing this news, Frank sent word to her with a proposal of marriage. In Calgary on April 16, 1898, they were wed. Together, they rode into the Selkirk Mountains in the Idaho panhandle where they spent 3½ years in a log cabin with an earthen floor, miles from any neighbours.

In 1901, they gave up that frontier life and moved to Ottawa, where Frank took up a junior clerk’s position in the finance department. With his wife Dot’s inheritance, they bought a double house at 25 and 29ÊRussell Avenue, living in 29 and renting 25. It may have been Dot’s desire to start a family in a warm home rather than in a log cabin that prompted the move, for they quickly welcomed three daughters into their family after settling in Sandy Hill. They lived on Russell untilÊ1951. After Dot’s death, Frank lived by himself in an apartment at 404 Laurier Ave. E. for two years. He then moved in with one of his daughters to an apartment at 292 Daly Ave. He lived at that location until his death in 1960; he was 96.

Frank was an all-round accomplished athlete and outdoorsman. He played baseball as a catcher, and he was a competitive foot racer, rower, and snowshoer. He also skied, curled, boxed, and golfed, and he played tennis into his eighties. A keen activist in sports administration, he served as President of the Ottawa Rowing Club and helped establish the Civil Service Athletics Association. From his position as its first president, he became a leader in the Canadian Amateur Athletic Union. He led the fight to stop professionals from creeping into amateur leagues. There was often more at stake than a simple win if a pro could help win a bet.

His organizing skills and his leadership were very quickly put to the task of assisting his fellow workers in the federal government.

Conditions of work were neither fair nor safe, and the key to getting a federal job was often political patronage rather than merit. Likewise, political patronage running in opposition to the ruling power was a way of losing a job. Wage increases were at the whim of departments and supervisors. One man only saw his annual salary raised from $1,200 to $1,600 over 26 years. Another went 21 years and only saw his wages rise $100. Between 1901 and 1907, the cost of living in Ottawa had risen by 20 percent.

In 1907, there was much excitement when a letter was circulated through the departments calling for the election of representatives to attend a meeting to form a union. On November 12 in the crowded Railway Committee room in Parliament’s Centre Block, they formed the Civil Service Association (CSA). The key organizers came from the ranks of the athletics association.

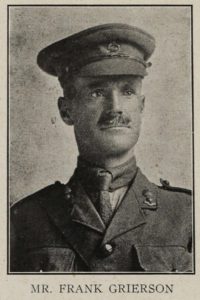

As the CSA was taking shape, Grierson with three others became the editorial board of The Civilian: A Fortnightly Journal Devoted to the Interests of the Civil Service of Canada, the first issue of which appeared in May, 1908. The Ottawa Printing Company proposed the idea to Grierson because of his reputation and stature in the service.

Photo Ken Clavette

There were risks involved in speaking out for employees of the Dominion government, however, and therefore anyone associated with the journal might well earn the displeasure of the government. While names of those on the editorial board did not appear in the journal, Ottawa was a small city, and it did not take long for their identities to become known. It probably didn’t help that the journal was run out of the Grierson home, which was just around the corner from Prime Minister Laurier’s residence!

Grierson quickly championed the unification of all federal workers into one union. In those days, the federal service was referred to as “inside Ottawa or outside.” The membership of the Civil Service Association was solely Ottawa based. Grierson pushed for a national organization. He published a draft constitution of what such a union would look like. He participated in the 1909 founding of the Civil Service Federation, the first national public sector union. In 1912, The Civilian was made the official voice of the Federation.

For the next eight years, Grierson would use his journal to champion federal workers’ rights. The biggest campaigns were for laws that would end political patronage. He believed such patronage made service to Canadians worse off. As a result of it, employment was tenuous, and those appointed were often unqualified. He acted not just with his pen and the printing press. He also was a leader in the Federation, serving on committees as secretary-treasurer (1913-1914) and as president (1918-1920). He was always pushing the Federation to act like a real union and join the Dominion Trades and Labour Congress. He helped force a vote in 1920 of all civil servants working in Ottawa in order to test the waters about joining the Congress. Despite the vote being open to anyone including deputy ministers, the results showed close to 60 percent wanted to be part of the broader labour movement. When the local leadership would not act, Frank became active in the short-lived Federal Union 66 that was chartered by the Congress.

When he retired from the CSF in 1920, its magazine The Civilian pointed out that his success in the department of finance “would probably have been better recognized had he been less active in the work of Civil Service organization. No effort to bring civil servants into closer mutual understanding and to unite for the common good has failed to receive sympathy and active support from Mr. Grierson, and in the main movement he has been a leader from the very beginning until now. Mr. Grierson was in very deed the father of Civil Service organizations.”

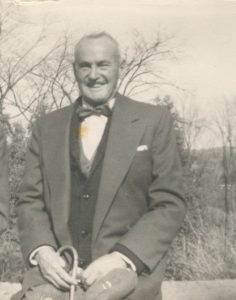

Photo: John Marshall

In 1949, the Ottawa Citizen wrote that “…without thought for himself as a civil servant, Grierson sacrificed prospect of permanence and promotion.” The paper believed he could well have become deputy minister of finance but for his “zeal and persistence” agitating on behalf of federal workers. He retired in 1930 as a Class II Clerk.

In 1966, with the federal government of Lester Pearson bringing in laws to allow for collective bargaining by federal employees, the organizations Grierson helped establish in the earliest years of the century came together as the Public Service Alliance of Canada.

Thanks to Frank’s great-grandson John Marshall for his assistance in my research. Ken Clavette.

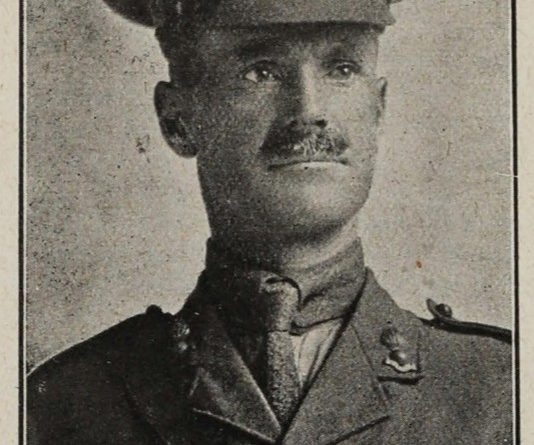

Grierson in uniform

Photo The Civilian

To understand the persistent nature or Frank Grierson, one need only look at his First World War record. He had been an officer in the Reserves, and now with war underway, he transferred to Second Ottawa Battery in hopes that he would be sent to Europe. He faced resistance from his deputy minister, who refused to grant him leave. Grierson even gave up his rank of captain in the Reserves to become a lieutenant, thinking that that would aid him in his quest. By 1915, he got his leave and sailed for England.

Commanders there had no intention of sending a 50 year-old soldier to the front, no matter how hard he pushed for it. He was put to work as a training officer. A lifetime of athletics, together with his qualities of leadership, earned him praise for his work. In November 1917, he was recalled, resuming his duties in the Department of Finance.

When Prime Minister Mackenzie King made it known in 1922 that his government was going to dismiss a large number of war veterans, a mass meeting was organized. Grierson was appointed the chair of a committee of veterans that successfully lobbied against that idea.