BOOK REVIEW

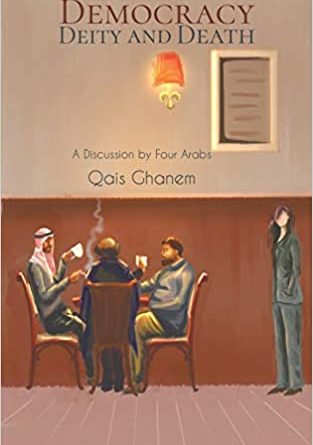

Democracy, Deity and Death

A Discussion by Four Arabs, by Qais Ghanem

London: Austin Macauley Publishers, Ltd., 2019. 131 pp

Maureen Korp

Qais Ghanem has written his best book yet. Author of seven books to date, Ghanem, long-time host of CHIN Radio’s talk show “Dialogue with Diversity,” sets forth a lively discussion in Democracy, Deity and Death.

The plot is straightforward. By happenstance, four people of Middle Eastern heritage, are seated at the same table in a London coffee shop. The coffee is good. The four are glad to be there. All are delighted to be able to talk frankly with one another, in English and Arabic, about events that matter – topics both practical and impertinent, real and theoretical. The conversation is timely and current: each individual arguing positions, sometimes impulsively, always authentically; each presenting arguments marked by humour, good will, and an abiding curiosity to know what the others will say.

The plot is straightforward. By happenstance, four people of Middle Eastern heritage, are seated at the same table in a London coffee shop. The coffee is good. The four are glad to be there. All are delighted to be able to talk frankly with one another, in English and Arabic, about events that matter – topics both practical and impertinent, real and theoretical. The conversation is timely and current: each individual arguing positions, sometimes impulsively, always authentically; each presenting arguments marked by humour, good will, and an abiding curiosity to know what the others will say.

Why, they wonder, is the Middle East such a mess? What’s going on in Syria? Iraq? Who’s in charge? Is Islam the problem? Arab media? Really? Is Christianity any better? Who says so? Who is chosen, really? To do what? Maybe the problem is government, the state’s use of religion? Is Lebanon truly multicultural? Human rights? Anyone know where to find a good bowl of mulukhiyah (Egyptian spinach), or what about some saltah (Yemeni lamb stew)?

Who are these four? One is a real estate agent, a young man called Sam, hailing from Lebanon. Another is a friend of his, Samia, a woman working as a bank officer. Samia’s family is Egyptian. She is divorced and a single mom. The third is her uncle, Saleh, an older man, newly widowed. He is a professor at the University of Edinburgh. The fourth individual at the table, Abdul-Raheem, born in the UK, grew up in Yemen. Abdul-Raheem is new to London. Fleeing Yemen and its civil war, Abdul-Raheem arrived back in the UK with a wife and four children in tow.

The author identifies three of the four characters as Muslim: Saleh, Samia, and Abdul-Raheem. The fourth, Sam, is tagged Christian. The reader is not told Sam’s Christian denomination, nor are we told with what branches of Islam the others identify. These omissions render each a stereotype for faiths that are, in reality, clusters of belief and practice whose differences matter much to the observant. Abdul-Raheem, for example, cites Sharia precedents often, but the reader does not know if his references are Sunni, Zaydi, or . . . ? Is Sam’s background Coptic Christian, or . . . ?

The writing is short, crisp, well-paced. The book opens with a wedding, followed by a car crash, and the death of the beloved. Near the end, the group discussion turns to death and whatever follows. How is one to know?

In London today, as in Ottawa, questions of origin are easily asked: “Where are you from? Really from?” Qais Ghanem’s novel asks better questions, worth all our attention. He permits his four protagonists to discuss questions of identity and the stereotypes of multiculturalism with wit, humour, and intelligence. In his introduction, Ghanem states that his own questions concerning death, and what happens then, first appeared when he was a medical student dissecting cadavers. Years later, having become a neurophysiologist, the author remembers these questions. We all ask them.