“We have met the enemy and he is us” –Pogo (Walt Kelly)

Dodi Newman

Our used and discarded clothing is stressing the capacity of North American landfills and has become a major pollution problem. So much so that the city of Markham, Ontario, no longer allows clothes to be placed at the curb for pickup. If we are serious about the environment, we need to buy fewer clothes, wear them longer, and make more responsible buying choices. And we need to start NOW.

The clothing industry and consumers spur each other on in an ever faster cycle of supply and demand. According to market research firm Statista, the Canadian apparel market was worth an estimated CAD$33.05 billion in 2016; and was forecast to increase to roughly 39.3 billion dollars by 2020. A report published by the World Resources Institute (www.wri.org) states, “The average consumer now buys 60% more items of clothing than in 2000, but each garment is kept for half as long.”

Photo Dennis Van Staalduinen

The result is used clothing waste. A US Environmental Protection Agency table for 2017 shows that the amount of clothing and footwear that went to landfills doubled from 6.3 million tons in 2000 to 12.5 million tons in 2017. In the same time, the US population grew less than 15%. Add to that, the fact that 65% of the fibres used to make clothing are petroleum-based – think polyester and acrylic – and can take hundreds of years to decompose, and it is clear that used clothing has become a major environmental problem. It is we, the buyers, who cause that problem. It is true, we are aided, abetted, and manipulated by the clothing industry, but surely we could say NO?

Dumping clothes in the trash is an appalling waste, not just of clothes but also of the natural resources it takes to make, transport, and dispose of them. The main resources are:

Water – On average, it takes 10,000 litres of water to produce one kilogram of cotton (Better Cotton Initiative – this is a low estimate). It also takes water to make polyester (petroleum-based) and viscose (wood-based) yarns. Every time we discard a piece of clothing, we waste water.

Petroleum, trees, and cotton are the main raw materials used in making yarn. Petroleum also fuels production and transport – raw materials, the finished clothing, and eventually used clothing. These are valuable and, in large part, non-renewable resources. They too are wasted when we throw clothes away.

Chemicals like dyes, fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides are used widely in the production of fibres. All of them are toxic pollutants. The World Bank estimates that textile dyeing and treatment (e.g. making clothes waterproof and fire resistant), contributes 17% to 20% of total industrial water pollution. Check out the Citarum River in Indonesia to see what the textile industry has done to it. When clothing is thrown away, that pollution remains.

The industry is beginning to respond to pressure from its customers to “use ethically sourced and green manufacturing materials,” according to Shopify. The internet is abuzz with statements from the clothing industry on how it will become more sustainable, and in fact, it has made progress. But the current state of science and logistics is nowhere near being able to truly re-process or re-use all those unwearable clothes. Meanwhile, the industry keeps producing; we keep buying; and the glut keeps getting bigger.

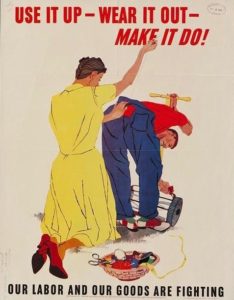

What can we, the consumers, do to lessen it? Back in the Second World War, the motto was “Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.” Today’s focus is on reusing and recycling, but these are not the solutions we like to think they are. According to Advanced Waste Solutions, Canadians now recycle only about 15% of wearable textiles. The US Environmental Protection Agency estimates that, in the US, 86.4% of discarded clothing ended up in landfills or incinerators in 2017.

What can we, the consumers, do to lessen it? Back in the Second World War, the motto was “Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.” Today’s focus is on reusing and recycling, but these are not the solutions we like to think they are. According to Advanced Waste Solutions, Canadians now recycle only about 15% of wearable textiles. The US Environmental Protection Agency estimates that, in the US, 86.4% of discarded clothing ended up in landfills or incinerators in 2017.

Most people recycle clothes by donating them to charities. If you do, please give some thought to how you do that. Charities like the Salvation Army and St. Vincent de Paul sell only 25% of what they are given, says Paul Jay of the CBC. Value Village is not a charity, but a for-profit company. Charities could sell more, if more of the clothes they receive were in good condition. How good? As the Salvation Army puts it, “If you would give it to a friend to use, then chances are The Salvation Army can use it.”

Here in Sandy Hill, we can donate our clothes to the Maycourt Bargain Box on Laurier Avenue East, a small store accepting only men’s and women’s clean, undamaged clothing of good quality; children’s clothing is not accepted. “Donations need to be good enough to wear out of the store,” Donna, a ten-year volunteer told me. As a result they sell most of what is donated.

What happens to the unsold clothes? It is difficult to get to the bottom of this. Some clothes go straight to the dump. Some of them go to brokers and wholesalers, who buy them by the truckload, sort them, and find buyers. Most are exported to developing countries, mostly in Africa. In 2017, Canada ranked eighth among the world’s leading exporters of used clothing and exported CAD$21.2 million worth to Kenya alone, says Statista. Some are-processed to make new textiles and pro ucts for industrial use. What wholesalers and brokers can’t sell goes – you guessed it! – to the dump.

What can we do to lessen the glut and keep all those clothes out of the dump? Buy used clothes instead of new ones. Alter them or find a local seamstress or tailor to fit new styles or waistlines. Keep them in good repair. Pass them along to friends or family. Use them as rags. Best of all, buy fewer clothes and wear them out.