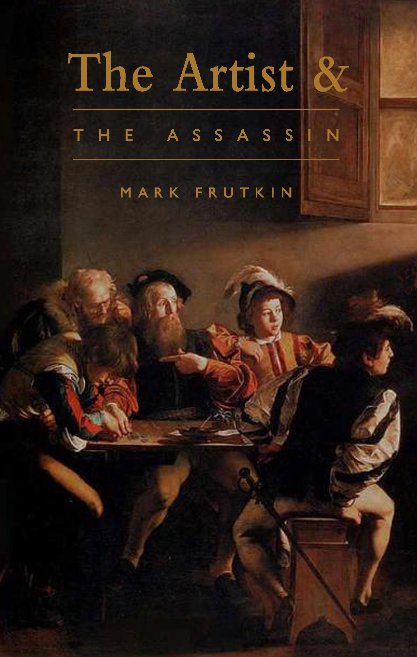

Book Review — The Artist and the Assassin by Mark Frutkin

Bill (Balwant) Bhaneja

Ottawa poet and novelist Mark Frutkin has written many works over the last 40 years, with novels mostly set in Italy and China. Frutkin is a fine writer—his offbeat creations steeped in history are written in lyrical minimalist prose.

Frutkin lived in a communal house in Sandy Hill from 1979 to 1985. From his second-floor office on Stewart Street, the seeds of his early books of poetry and novels were sown, including: The Growing Dawn (1983), Alchemy of Clouds (1985) and Atmospheres Apollinaire (1988), which was nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Award and the Trillium Award.

Frutkin’s latest novel, The Artist and the Assassin (2021) is about the leading Italian painter of the 16th century Michelangelo Merisi, also known as Caravaggio, and is set in early 17th century Italy, moving from Rome to Naples to Malta, and then back to Naples.

The story of an intemperate artist and his assassin Luca is about revenge and retribution in which the victim is unaware that he is the object of someone’s hate and envy, when the preoccupation of the artist is to find a perfect light in his paintings.

Frutkin weaves his narrative through light and darkness in Caravaggio’s art: “Strangely the dark parts brighten the light. On the other hand, the light makes the darkness deeper and deeper. As if he has given us a view into his soul.” (p.92). He calls this: “Chiaroscuro – a mixing of light and dark. Yes, like life and death.” (p.93).

Frutkin writes about Caravaggio’s work: “His canvas a bit of theatre, a scene from a play. […] wildly dramatic about it, the way the light stands out from the dark.” (p.92).

The assassin’s chase tells the reader about society when Italy was brutal and stratified, structured with inequalities that produced rampant corruption and erratic violence. Frutkin informs us about the difference between Caravaggio’s large canvasses and reality; it does not resemble religious paintings at all. His models are street people, dressed up to look like what they are not. Luca is surprised by Caravaggio’s choice of him as a model for his paintings, especially as an emaciated Jesus on a wooden cross.

Luca’s model is a poor street scrapper, a mercenary rapier unknown to the artist. Doomed to suffer, he embodies fear of the street. Resentful and uncaring of sorrow, he mocks the pretense and idolatry around him. Unknown to Caravaggio, he has a contract to kill him for a mistaken killing of a noble’s son.

The tightly written novel with a narrative that alternates between the voices of its two protagonists, more intimately describes Luca’s angry condemnations. Revelation of Luca’s hidden humanity comes through in a flash of anger towards the end when he is about to assassinate the artist. He notes that even in a semi-unconscious state, a vexed Caravaggio is desperate to retrieve his paintings—his sole concern being whether he will be able to repeat the light he created over his lifetime in his drawings. Anguish in Caravaggio’s shiny bright eyes gives Luca, for first time, a glimpse into the mind of the artist. His rage for the artist suddenly dissipates, wanting to become Caravaggio’s saviour.

The book is beautifully laid out with graphic-style images of period engravings from Picturesque Europe (1879) by Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London.

An exquisite work.