Ken’s Bygone Sandy Hill

Why was a uOttawa residence named after Hubert Brooks?

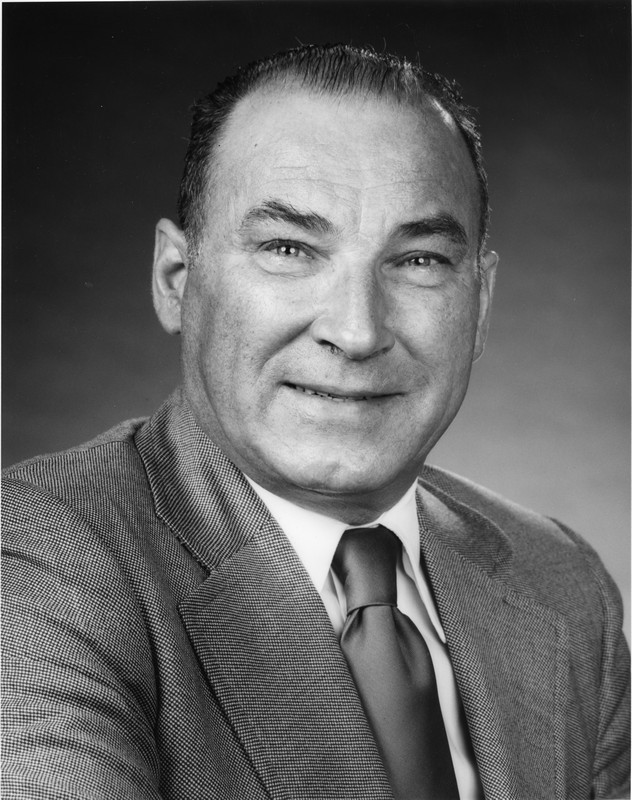

Ken Clavette

Lately there has been much debating about naming things like streets and buildings. This naming of buildings has a long history. As far back as the first century, the Roman general, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, had his name inscribed on the Roman Pantheon which he had commissioned. Governments name buildings after politicians and rulers, cities after prominent citizens or, in the case of Ottawa, British colonial politicians. Universities lean towards naming their buildings after large donors. Mostly the people in Sandy Hill walk by the buildings at the University of Ottawa and have no knowledge of why the name was given.

Photo Ken Clavette

A few years after my family settled in Sandy Hill, demolition began of the boarded-up homes on the block, near my home, bounded by King Edward Avenue, Marie Curie Private, Copernicus Street, and Thomas Moore Private. Soon a complex of low-rise apartment units, a parking garage, and an institutional building rose from the hole in the ground. What was to be called the “Brooks Complex” started accepting 708 students in the fall of 1987. Over the past 37 years I have, from time to time, wondered who this “Brooks” was? That curiosity increased since the buildings have been shuttered and unoccupied for the past 5 years.

It was easy enough to learn that the complex was named after Hubert Brooks, the first full-time Director of Housing Services for the university. Quite an honour for an employee of the university I thought. There must be more to the story, and there was.

Mr. Brooks was an innovator in housing development in Sandy Hill. He was a key driver of turning over neglected and costly houses the university had acquired on King Edward and Henderson Avenues to the Sandy Hill Housing Co-op. The co-op brought 100 new residents into our community in 1984; they were great neighbours. But his larger plan was to use the lease of university land to this not-for-profit housing group to help fund the complex that came to bear his name. Again, quite an honour but there had to be more to the man. My research gave me an amazing story to tell.

Hubert Brooks was born on December 29, 1921, in the small rural community of Bluesky, Alberta. I say small because even today the population only numbers 133. Bluesky is in Peace River country, 568 km from Edmonton, but only 161 km from Dawson Creek, BC. During the Great Depression his family moved to Montreal where he was educated in French and became skilled in hockey. In 1940 the 19-year-old did what so many of his generation did, he joined up to fight in the Second World War. He chose the Royal Canadian Air Force, graduating in August 1941 as a navigator-bomber. Arriving in Britain in February 1942, he was assigned to 419 Bomber Squadron. On April 9, on his second bombing raid, his plane was shot down near Oldenburg, Germany, and he was taken prisoner of war.

Held in Stalag VIIIB, a German Army-administered POW camp, he switched identities with a New Zealand Army private because airmen were not permitted to be on work details that could leave the camp. After several failed escapes, enduring the punishment of severe beatings and solitary confinement, he finally made it out and was smuggled into occupied Poland. His skills as a navigator combined with any map he could get his hands on made his final escape a success.

In 1943, he and a fellow escapee, a Scottish soldier, were in contact with the Polish underground. Rather than be smuggled out of the country, both men made the dangerous decision to stay and become freedom fighters. Dangerous because if caught the punishment now would be execution. Posing as a Polish labourer he took part in night patrols, sabotaging convoys, and assassinating members of the Gestapo. Eventually he was promoted to second lieutenant, leading a resistance unit. He earned the Polish Cross of Valour for his exploits. By January 1945 the allies were making gains. The Russians liberated Warsaw, and he made his way to the Russian front line, eventually making it to London in March. He was able to return to Canada in June 1945. He was awarded the British Military Cross in recognition of “acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy on land.” Poland awarded him their Cross of Merit with Swords for “deeds of bravery and valour.”

Brooks continued his air force service in a unit looking for individuals recorded as missing or killed in action. The work included hands-on searching in Denmark and Norway. While in Scandinavia he played hockey during his downtime as a member of the U.S. Army Allstars. As Canada prepared for the first post-war Olympics in St Moritz, Switzerland, in 1948, Brooks was selected to be a member of Canada’s hockey team. The team, known as the Ottawa RCAF Flyers, was made up entirely of members of the RCAF. He didn’t get any ice time but was proud of several things: his Gold Medal, being the nation’s flag bearer during the opening ceremonies, marrying his fiancée Birthe the day after the Canadian victory; Barbara Ann Scott, Canada’s figure skating gold medalist, was Birthe’s bridesmaid. Their honeymoon was delayed as the Ottawa RCAF Fliers did a European Tour, winning 34 of 40 games played. Brooks, along with the rest of the Flyers, was inducted into the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame in 2008.

Following the war and Olympic glory, his life was his family and continuing to work in the RCAF. He served at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) in Belgium, RCAF station in Moisie, Quebec, and Army Headquarters in Ottawa. Retiring in 1971 after 31 years of service he joined the administration at the University of Ottawa, eventually becoming its first Housing Director. While sitting at his desk on February 1, 1984, he suffered a fatal heart attack, he was only 62.

That’s who Hurbert Brooks was, and why in 1988 his name was given to a uOttawa residence. A war hero, Olympic champion, and a man who helped build community and student housing in Sandy Hill. As the university ruminates over the future of the Brooks Complex the residence remains shuttered. The housing Co-op he helped settle here has been given notice of eviction. On June 16, 2023, the Brooks family were on hand when the plaque that was once associated with the residence was moved to the foyer of a newer, more modern residence (called “90u”). Instead of a building, there is now a Hubert Brooks Foyer.

His son has written an online biography at www.hubertbrooks.com.

Photo: uOttawa Fond 6, AUO-PHO-MB6-2477